Polyrhythmic Programming in Ableton Live 9

Noah Pred on Oct 10, 2013 in ABLETON LIVE • 0 comments

There's grooves and then there's grooves. In this tutorial, Ableton Certified Trainer, Noah Pred, shows how to take your Ableton Live 9 groove creations to the next level polyrhythmically.

When a groove really hits home, people talk about it being in the pocket – but where is this pocket everyone's talking about, and how do we find it? In this tutorial, we'll look at some tricks using Live 9's enhanced MIDI editor to help build syncopated grooves that mesh together like a jigsaw puzzle, building rhythms that seem as though they couldn't exist apart from each other.

First things first

I'll start by creating a very simple four-to-the-floor house beat in a Drum Rack, with kicks on all quarter notes, claps on the two and the four, and a 2-bar pattern of upbeat hi-hats, with a few 1/16ths thrown in for added feel (Pic 1). We'll use this basic drum pattern to anchor the rest of our set.

Pic 1

Next, I'll use an instance of Operator to write a bassline. I'll try to write things here in the key of E minor, but that's beside the point – you can carry out this exercise in any key or scale, and use the Scale MIDI effect to force your notes to a chosen scale. It's important we do everything in 1/16th note quantization intervals from here on out.

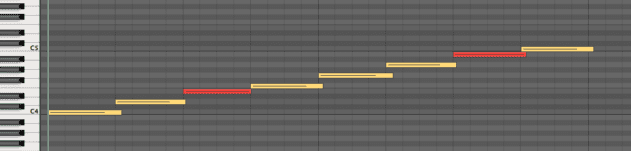

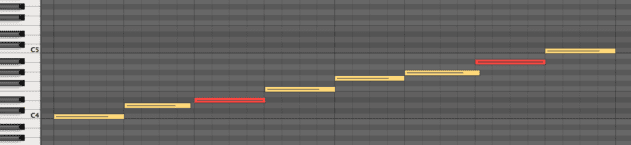

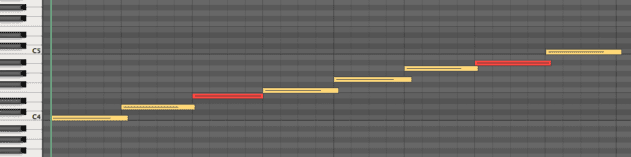

You can record the bassline in via MIDI keyboard, or write it into an empty MIDI clip using the draw tool. I've just recorded in a one bar bassline (Pic 2), but I want to make it a bit more dynamic, so I'll click the loop brace and hit Command-D (or click the Dupl. Loop button in the Clip Note settings area) to make the loop 2 bars (Pic 3).

Pic 2

Pic 3

Now that I've extended the duration of the loop, I can add a note to the second bar to make it a little more interesting (Pic 4).

Pic 4

Getting Interactive

Now that we have a bassline in place, we can begin to build a groove around it. I've created a new MIDI track using the Organ 4 Dance preset. Now I'll copy and paste (oroption-drag) the bassline MIDI clip into an empty clip slot on our organ track.

Within the newly copied clip, I'll select all the notes, hold down the Shift key, and use the up arrow buttons on my computer keyboard to move all the notes up an octave at a time – a nice little trick enabled by the Shift key modifier. In this case I've shifted them up a single octave.

Next, I'll select them all again and strike the zero (“0”) key on my QWERTY keyboard to deactivate all the notes: they can now function as “place holders” to remind us where the bassline notes are located. Finally, I'll hit the fold button to the upper left of the Note Grid to ensure we don't program any notes outside the original key (Pic 5).

Pic 5

I'll now use the draw mode to write new MIDI notes into the organ clip, being careful not to draw any in on the same rhythmic intervals where we already have notes in the bass line (Pic 6).

Pic 6

PRO-TIP: To give it more “vibe”, I'll add a Chord MIDI Effect to make the organ trigger more than just a single note. I'll also adjust the instrument filter settings until it fits a little better (Pic 7). Feel free to add more effects, via insert or send, as needed.

Pic 7

And Again

I'll essentially repeat this process two or three more times until I have a full groove built up, each time copying the most recently added MIDI clip and deactivating all the notes before adding more notes in the remaining empty note slots. The first time, I'll use a sort of analog acid synth (Pic 8).

Pic 8

Finally, I'll use an Electric Rhodes MKII patch.

Pic 9

Superstructures

This process doesn't really apply to sustained atmospheric sounds, so feel free to add those later; this is more of a creative technique for building rhythmic, syncopated grooves from scratch using some of the handy new features of Live 9's MIDI editor. If you're looking for a strategy to help your sounds sit better in the mix by not overlapping, or just need new creative technique to employ when other ideas aren't flowing, this approach should prove helpful indeed.

Take a listen to all tracks together: